MANILA, Philippines -- Imagine standing in the middle of an urban landscape pullulated with towering buildings, crisscrossing bridges and highways, unnerving cacophony of car engines, obtrusive signage glaring with neon lights, lofty billboards with half-naked women endorsing products, harried faces and footsteps scurrying on busy streets, stray cats and dogs walking and sniveling along the squalid pavements and alleyways.

Now, in a more claustrophobic ambience, imagine standing in the middle of a 20- square-foot art gallery filled with conspicuous images, signage and neon lights, albeit some art pieces are confined either within glass boxes or behind transparent acrylic panels. Texts and images become alive through the three-dimensional objects, coiled neon lights on the wall, and projected video on the floor.

Some images may conjure up nostalgia and decay. For instance, an emaciated bonsai tree bereft of leaves, a stone engraved with Latin words, or a sepia photograph of children sitting on the rocks by the sea. Other images may elicit psychological tension, like a wooden religious statue without a hand, an airplane about to take off, or a neon-lighted typeface that reads “perfection” with unlit letter “n.”

How such poignant imageries create a poetic and conceptual landscape in the human mind and senses is the ingenious creation of a literary iconoclast -- poet and conceptual artist Cesare A.X. Syjuco.

A Brief Glimpse on the History of Conceptual Art

In an 1885 foreboding novel “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” written by the proponent of existentialism the 19th-century German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844 –1900), a madman cried: “Gott ist tot!” or “God is dead!” Thereafter, that controversial avowal of God’s death would change the course of man’s perception of God and the world, and, later, reshape the history of art and literature from a spiritually- centered quest for beauty to a more concrete affair in the secular world.

In 1917, three decades later after Nietzsche’s stark criticism on Christianity through his novel and philosophical writings, another ‘death’ was foretold and this time, the imminent death of classical art in the form of “urinal.” Precursor of conceptual art the French artist Marcel Duchamp (1887 –1968) transformed an ordinary readymade urinal into an objet d’art titled “Fountain” signed with his pseudonym “R. Mutt.”

From there, Marcel Duchamp paved the way for modern and postmodern art movements throughout Europe, America, and Asia, particularly the theoretical development of conceptual art. American artist Joseph Kosuth would later acknowledge Duchamp’s important role in conceptual art when he said that all art, after Duchamp, is conceptual in nature because art only exists conceptually (1969 essay “Art after Philosophy”).

But Conceptual Art did not emerge as a movement until the mid 1960s, with the notion of elevating and transforming any idea or concept into an artistic form using found and readymade objects, as auxiliary devices to the theoretical and conceptual approach of art making. Conceptual art, per se, subverts the conventional form of aesthetics with limitless possibilities –- dynamic, transformational and interactive.

Contrary to Dadaism and Surrealism that defy reason with emphasis on chance and the supremacy of dreams, conceptual art celebrates reason and sensual perception, imploring the participation of the audience to deduce and complete the meaning of any presented works (assemblages or installations) by the conceptual artists.

Some well-known practitioners of conceptual art across the globe are Robert Rauschenberg (1925 –2008), Solomon "Sol" LeWitt (1928–2007), Walter De Maria (1935–), Robert Smithson (1938– 1973), Lawrence Weiner (1942–), Joseph Kosuth (1945–), Jenny Holzer (1950–), and Damien Hirst (1965 --), to name a few.

In the Philippines, the forerunners in their own respective styles and tendencies are David Medalla (residing and creating his art in different continents), Roberto Chabet, and Cesare A.X. Syjuco, among other senior and younger generation of artists who are swinging between painting or sculpture and conceptual art.

Perhaps, one of the powerful and influential bodies of works in the Philippine art scene that span three decades of art making, which is more than any Filipino contemporary conceptual artist could ever produce in his or her lifetime, is Cesare A.X. Syjuco’s works. His art is the crossbred of visual art and literature, mimicking literary texts and mass media campaigns.

Although Cesare A.X. Syjuco refuses to be labeled with any aesthetic style and genre, his artistic practice is the embodiment of conceptual art -- socially relevant, jarring and intellectually confounding. His works are reminiscent of an American conceptual artist Joseph Kossuth. But unlike Kossuth, who uses an open space to designate the elements of his works, Syjuco uses a defined space within space to collocate the binary elements of his compositions in a cohesive and logical manner.

Known as “Literary Hybrids,” Syjuco explores multifarious combination of literary and art references through his collocated “texts” and “visual” images. In the form of ‘media-collocation,’ he meticulously gathers selected elements (texts, images and objects) for his composition, meld and interlock them together within glass boxes or rectangular transparent acrylic panels, with the exceptions of neon lights and video projections that have found their respective spaces on wall, floor or ceiling.

By fusing literature and visual art, his opus is an acerbic commentary on global culture, politics, commercialism and technology, imbued with witty intellection, irony and humor.

The Quiddity of ‘Concept’ and ‘Object’ in Conceptual Art

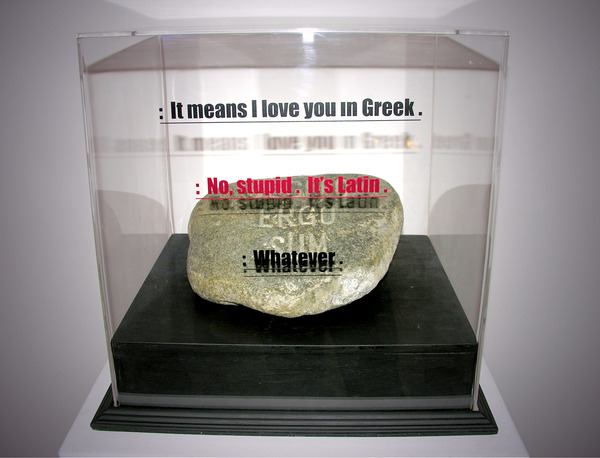

In his 2010 exhibit, The Ancestry of Stone, at Gelleria Duemila, Cesare A.X. Syjuco carved “Cogito Ergo Sum” on a semi-flat stone and encased it inside a glass box. On the frontal surface of the glass is a phrase that reads: “:It means I love you in Greek. : No, Stupid. It’s Latin. : Whatever.” Judging from the two inscriptions both inside and outside the box, one can deduce an ostensibly out of context statements with no correlation at all.

A closer look, however, reveals a subtle yet humorous way of anticipating the viewer’s reaction in case they fail to understand the Latin text inside the box. Their anticipated response is subliminally fed in their mind through the readymade answer outside the box. In this regard, the text serves as a point of reference (terminus a quo), vis-à-vis, to the text inside the box (terminus ad quem).

On the contrary, although both textual contents within and outside the box are both syllogistic concepts of the artwork yet, either one can become an “object” referring to each other’s symbolic meaning, depending on the subjective interpretation of the viewers. Although, the artist has already laid out the concept of his art yet, he also considers the ‘variables’ of interpretation: How the different viewers of diverse backgrounds, for example, might perceive his work as a whole.

By providing a readymade answer outside the box, the artist wittingly engages the viewers to think beyond the ‘quiddity’ of an object and examine how it represents the concept of his composition. ‘Quiddity,’ by definition, comes from Latin “quidditas” (root words “quid, quis” or “who/what”), which refers to the “whatness” or “thingness” of an object or concept before it is used as a symbolic representation.

The ‘quiddity’ of an object, as employed by this writer in conceptual art, is independent of the concept, but when it is used and conferred upon with artistic value, the object transforms its “whatness” and assumes a new epistemic meaning. What precedes the object is the main concept or idea of an artwork. Hence, the ‘quiddity’ of an object is always relative and variable congruent to the “concept” that it represents.

But even the quiddity of any object or concept can assume its own locus when presented as an objet d’art contingent upon the ‘primum intentione’ (objective) of the artist.

For instance, in Marcel Duchamp’s urinal, the artist blatantly presented the object as a work of art, no more no less, bereft of any symbolic meaning. In this manner, the quiddity of urinal becomes both the terminus a quo and terminus ad quem, the literal and the symbolic, the subject and the predicate. Considering its novel and innovative presentation, Duchamp’s urinal has become both the material and final cause of aesthetics in its highest form, comparable to the renaissance and classical art or any contemporary art, for that matter.

In Cesare Syjuco’s “Cogito Ergo Sum,” he uses the quiddity of objects, e.g., stone, glass box, and ‘auxiliary text,’ to amplify his concept in a transformational and interactive manner. Similarly, the textual contents inside and outside the box interchangeably complement and play both as “concept” and “object,” depending on the construal of the viewers. What is outside the box can be an auxiliary object to signify the concept inside the box, or vice versa.

For the viewers who are familiar with philosophers, they can immediately tell what inside the box (“Cogito Ergo Sum”) signifies by associating it to a French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes (1596 -1650). And, of course, “Cogito Ergo Sum” means “I think, therefore I am,” known also as a ‘Cartesian doubt,’ a methodological skepticism in rationalizing the truth of one’s existence or the truth in relation to God.

But for the viewers who are alien to both philosophy and Latin language, the text inside the box can be abstruse and inconsequential. While the text outside (:It means I love you in Greek. : No, Stupid. It’s Latin. : Whatever) provides a readymade answer to the ‘what and why’ of the artwork as it percolates through their mind and senses. In fact, what is written outside the box is surreptitiously intended for them in a cynical manner.

Hypothetically, to put it in a dialogic conversation, imagine three best friends discussing about the text (Cogito Ergo Sum) inside the box. Friend A says ironically, “It means I love you in Greek.” Friend B who feels intelligently superior among the three replies, “No, Stupid. It’s Latin.” But friend C, who does not give a damn what friends A nor B thought, exclaims, “WHATEVER.”

Arguably, that is precisely the point of the artist!

(Cesare A.X. Syjuco’s solo exhibit “A Life of the Mind” is ongoing at Galleria Duemila, 210 Loring Street, Pasay City, Philippines.)

*Published in Manila Bulletin Lifestyle (Arts & Culture), March 26, 2012, p. E1-2

I HAVE been reading and re-reading this book called Reading Literature Today, which is composed of, as the cover puts it, “Two Complementary Essays and a Conversation.”

I HAVE been reading and re-reading this book called Reading Literature Today, which is composed of, as the cover puts it, “Two Complementary Essays and a Conversation.” Centuries of traditions and traditions of aesthetics have created a fissure between the picture and the words. One can conjure art from pictures, from images or simulacra. From words and with words, one can create texts and, in so many ways, communicate. Images through art send messages but the layperson perceives in the addressing a mediation, an intervention of feelings and interpretations. With texts, one can merely, as in directly, read. Or so we all naturally think.

Centuries of traditions and traditions of aesthetics have created a fissure between the picture and the words. One can conjure art from pictures, from images or simulacra. From words and with words, one can create texts and, in so many ways, communicate. Images through art send messages but the layperson perceives in the addressing a mediation, an intervention of feelings and interpretations. With texts, one can merely, as in directly, read. Or so we all naturally think.